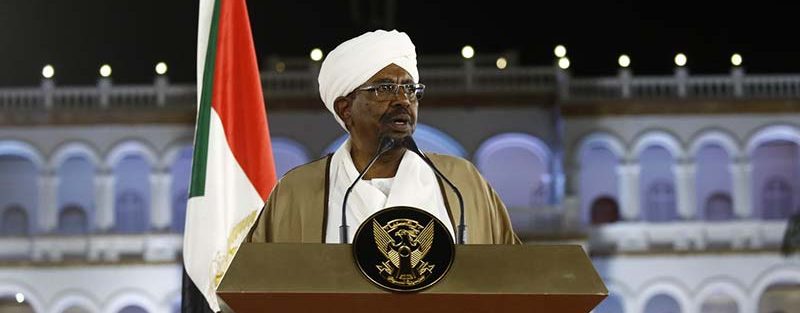

Will Al Bashir Ever Stand Trial at the ICC?

By Mohammed Elgizoly Adam

The purpose of this article is to analyze the possibilities of transferring Omar Al Bashir, the former president of Sudan, to The Hague. Since war erupted in 2002 in Darfur the former administration of Al Bashir had violated all jus cogens norms. Grave violations of international human rights and humanitarian laws occurred in Darfur at the end of 2002. War crimes, crimes against humanity, and possibly genocide had been committed. At the end of 2002, the Darfur Region of Sudan witnessed one of the worst humanitarian crises in 21st century.

To avoid the Rwanda’s genocide scenario the international community had to act swiftly. Hence the UNSC acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter adopted the Resolution 1593 on 31 March 2005, and thus referred the situation in Darfur, Sudan to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (hereinafter the Court) based on article 13 (b) of the Rome Statute. In 2019 after civil unrest and protest, Sudan entered into a transition government which brought with it a new challenge on the prosecution process.

The purpose of this article is to assess whether the newly formed Sudanese government may or may not transfer the former president of Sudan general Al Bashir to the ICC. Secondly, the article will analyze the capacity of the Sudanese legal system to try a powerful defendant such as Al Bashir.

Under UNSC Resolution 1593, Sudan is under the same obligation to cooperate as any other State party to the Rome Statute. It seems that the complementarity principle might be a legal basis for Al Bashir to stand trial in Sudan. As the prosecutor stated in her twenty-ninth report to the UNSC on 19 June 2019:

“The office recalls that in accordance with the principle of complementarity, the primary responsibility to investigate and prosecute crimes under the Rome Statute rests with States. The office stands ready to engage in dialogue with the authorities in Sudan to ensure that persons against who warrants of arrest have been issued faces justice, either at the ICC, or in Sudan.”However, because of the legality principle the complementarity clause can be problematic. According to Article 17, the court can only exercise its jurisdiction if the State concerned is unable or unwilling. The International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur in its report 2005 explicitly stated that the Sudanese legal system is unwilling and unable to address the atrocities committed in Darfur.

Further, the Commission of Inquiry concluded that the Sudanese justice system has been impaired during the former regime because it incorporated laws that confer broad powers to the executive branch that weakened the judiciary branch. Besides, currently, there are laws in force that violate primary human rights standards. Also, the Sudanese criminal laws do not sufficiently proscribe grave human rights violations such as war crimes and crimes against humanity that occurred in the Darfur region as well as the Criminal Procedure Code encompasses rules that make effective prosecution of such crimes impossible.

Moreover, according to Mohammed Abel Salam Babiker, since the civil war erupted in Sudan, there have been several changes in military laws that regulate the conduct of the National Armed Forces such as the legislative changes in November 1983 and June 1999. Babiker. M.A concluded that before the intervention of the ICC, Sudan’s military laws could not proscribe any violation of international humanitarian law. He added that apart from the fact that the former regime was evidently undermining the legal system, the national courts were unable to prosecute such crimes related to violations of IHL.

After the referral of the situation of Darfur, the former regime had made some amendments concerning the 1991 Criminal Act, and the Armed Forces, where war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide have been incorporated. However, according to Dr. Babiker. M.A, despite the significant aspect of the amendment, still the new legal reform does not adequately define crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide as internationally recognized or defined.

For these reasons, the inability of Sudan to prosecute Al Bashir is evident; given the capacity of the Sudanese legal system, the competence or the independence of the judges and witness protection, as well as the nature of the crimes committed, which are alien to the Sudanese legal system. For these reasons the complementarity principle might not be reasonable grounds for trying Al Bashir in Sudan.

Concerning the unwillingness in an interview with the France 24 Arabic Channel, Sudan’s new prime minister, Abdallah Hamdok, explicitly verified that the new administration is going to make a legal reform to make sure that the justice system is independent and capable to prosecute the crimes committed in Sudan. However, he stated that “Al Bashir will be tried in Sudan, and we do not accept any dictations from outside”.

There is no reasonable ground for such a speedy trial as in the case of Al Bashir. As Amnesty International elegantly embedded it “his case must not be hurriedly tried in Sudan’s notoriously dysfunctional legal system”. Sudan’s Deep State still functions, particularly in the judiciary branch. Currently, Al Bashir is charged with corruption, after the downfall of his regime. For example, his defense team consists of 96 lawyers, and all of them are prominent affiliated with the Brotherhood organization and the former regime.

In addition, the transition government could have at least charged him with the disproportionate use of force against the protesters during the period of December 2018 to April 2019, in which more than 70 civilians perished. It is evident that Al Bashir had the intention to remain in power at any cost; when he ordered his general to kill all the protestors gathering at the military headquarter. He justified his decision on the basis of Islamic jurisprudence that the leader may kill 30 to 50 percent of the population in order to save the rest.

It might be argued that it is more just for the defendant to face justice in Sudan so that he can be judged by the same law that he undermined and do time with the same people who are the victims of his unjust policies. However, Al Bashir case is quite different because it is symbolic for the millions of the victims of the civil war in the Darfur, Blue Nile and Nuba Mountains.

From an internal political point of view, Al Bashir might be considered as a liability not only to the new administration, but to all main political actors. Hence having Bashir out of the game; might be in everyone’s interest. Given, the hostile positions of some of the regional and international actors such as the African Union (AU) towards the Court, the transfer of Al Bashir could be complicated.

Hence it is likely that the AU may oppose any move of transferring Al Bashir to The Hague. Additionally, although the United States of America (US) initially supported Resolution 1593, it remains hostile to the Court. Therefore, the US might either abstain with the transfer or indirectly oppose it.

To conclude, given the isolation of the state of Sudan from world politics, economic sanctions that have affected the whole country, the mass victimhood, and the outcry for peace and justice across the country; the newly formed transitional government should have considered Al Bashir as a liability. Besides, it is evident that the primary obstacle to the new administration is the peace process in Darfur, in which Al Bashir’s case constitute an integral part of the process. Thus, for the new administration to prove itself as “a peace loving State” it has no other option, but to hand over Al Bashir to the ICC.

More information is available from Mohammed Hassan, Executive Director, DNHR.

Email: [email protected]

Phone: (+256)752792112 or (+249)924638036

P.O. Box: 144218